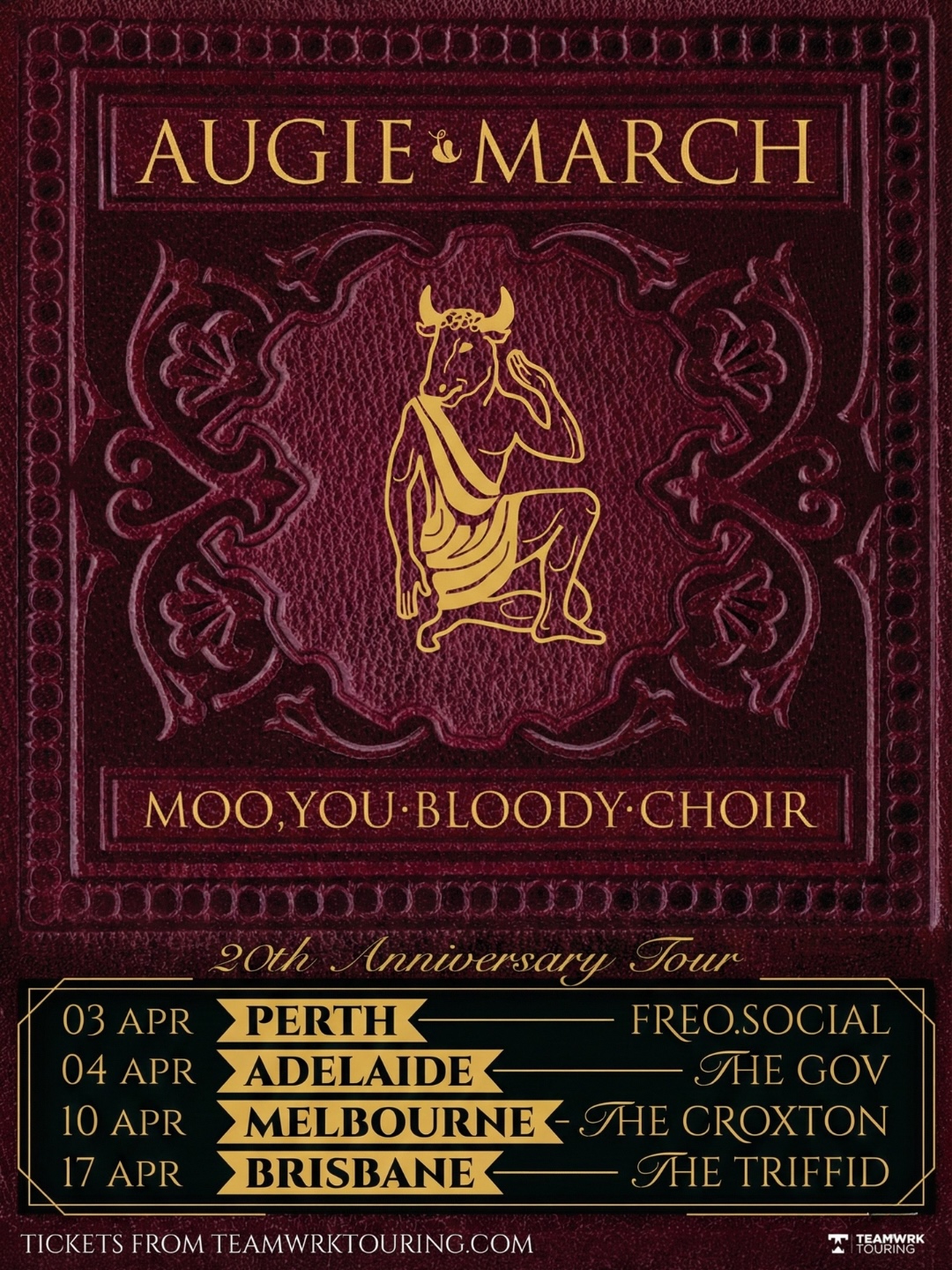

How does it feel to return to Moo, You Bloody Choir two decades on — not just as musicians, but as people who’ve lived a lot of life since that era?

The prospect of these anniversary concerts mainly makes me feel old and scared of looking in a 20-year-old mirror. It can be hard and confronting to try and relive or recreate something from so long ago. But once we get started, it will quickly become fine and even enjoyable.

When the album first came out, did you have any sense it would become such a defining moment in Australian music, or has its legacy only become clear with time?

Absolutely not. Is it really a defining moment in Australian music? That’s very nice of you to say. The album had actually been completed almost a year earlier and shelved indefinitely by the label. We were mainly just relieved to have it released at all, which meant we could start playing live again to promote it. When your label puts your finished record in mothballs, your thoughts go more towards survival, not so much about creating musical history.

One Crowded Hour changed everything for the band almost overnight. How do you remember that sudden shift into the mainstream and the impact it had internally?

It was the middle of summer when the song came out. It was quickly added to high rotation on JJJ, which was a big deal for us, but that didn’t result in any drastic, immediate overnight change. By the middle of the year it was starting to get played on commercial radio, and that’s when the queues at the shows started to get longer, the venues started to get bigger, and we were adding extra nights. It was like a big cushion of warm air pushing up from underneath. After many years of struggle, I thought that felt great. Not everyone in the band enjoyed it though — the spotlight and the pressure maybe weren’t a positive thing for the band overall.

The album moves between poetry, tension, softness, and ambition in a way that still feels unique. What creative risks or instincts shaped that sound during the recording process?

That range of dynamics came pretty naturally to us, and of course a lot of it is in the songwriting. The unique sound of the band had evolved over the previous ten years. I don’t think there was much deliberate intent or instinct to shape the album’s sound. Occasionally we did try to create a jarring sonic effect, like recording the piano via a guitar amp on Mother Greer. We attempted a slow, moody version of Frownland by Captain Beefheart, which is a very fast, jerky, and discordant freak-out song. That was creatively risky, but it didn’t get very far.

Parts of the album were recorded in the Tenderloin during a pretty intense period. How did that environment influence the atmosphere or emotional weight of the record?

Interesting. Yes, it was a very rough and sketchy neighbourhood. Historically, police who worked the beat there were paid an under-the-counter bonus of the choicest steak cuts, hence the name (this was in San Francisco, not Chicago). There was a gun murder close to where we were staying. However, the only three finished tracks from those sessions were arguably the poppiest songs on the album — One Crowded Hour, The Cold Acre, and Just Passing Through. In fact, we re-recorded The Cold Acre later in Melbourne; the Tenderloin version was actually faster and more upbeat. Maybe the environment didn’t have a big, direct influence on the music. One of the band members did fall in love, which might have added to the positive vibes.

There were label changes, personal challenges, and moments where the project felt like it might never come together. What kept the band anchored during that chaos?

Hmm. I’m not sure how “anchored” we were. Is it possible to be anchored by alcohol? Anchored in alcohol, perhaps. We were all very committed to the band, and there was definitely a lurking sense that this album was our last chance with our record label and our last chance to make a big splash with a mainstream audience. We had just done a seven-week tour of the US, which was by far the longest tour we’d ever done. We were getting road-hardened and match-fit, playing consistently good shows. That probably did give us some sense of confidence. In the past, our live shows had sometimes been erratic or unpredictable.

Fans often say the album “stays with them.” Which songs have stayed with you the most over the years — and why?

Not One Crowded Hour. I got very sick of that eventually, which is fair enough — that song has been played to death. I always liked Clockwork, the long, slow, heavy song at the end of the album. Stranger Strange is great too; that maybe could have been a hit single as well.

Performing the album front-to-back for the first time is a huge moment. What excites you most about presenting it as one complete, intentional body of work on stage?

The most interesting part is that we’re all very different people than we were twenty years ago, so there’s a good chance it will be a very different album of songs when we re-interpret it. It’s unlikely to be a musical carbon copy of the way we played it in 2006.

Revisiting this era must naturally stir new ideas. How does looking back at this album shape where you want to take Augie March next?

It probably doesn’t. The band has maintained quite a productive output, releasing four albums in the last ten years. Glenn has made a solo album as well and is in the middle of another one now — he still has a lot of songs. Doing an anniversary tour feels like something separate. When we revisited the band’s first album Sunset Studies five years ago, it overlapped with making a new album (Bloodsport and Porn). For a while Glenn was toying with the idea of that being Sunset Studies Vol. 2, but it didn’t eventuate. I can’t see us making Moo You Bloody Choir Vol. 2.

You’ve described the upcoming shows as a balance of respect and irreverence toward the songs. What does that actually look like when you’re all on stage together?

It could look like everyone treating the songs with great respect, whilst personally taunting and abusing each other with mild contempt — both on and off stage.